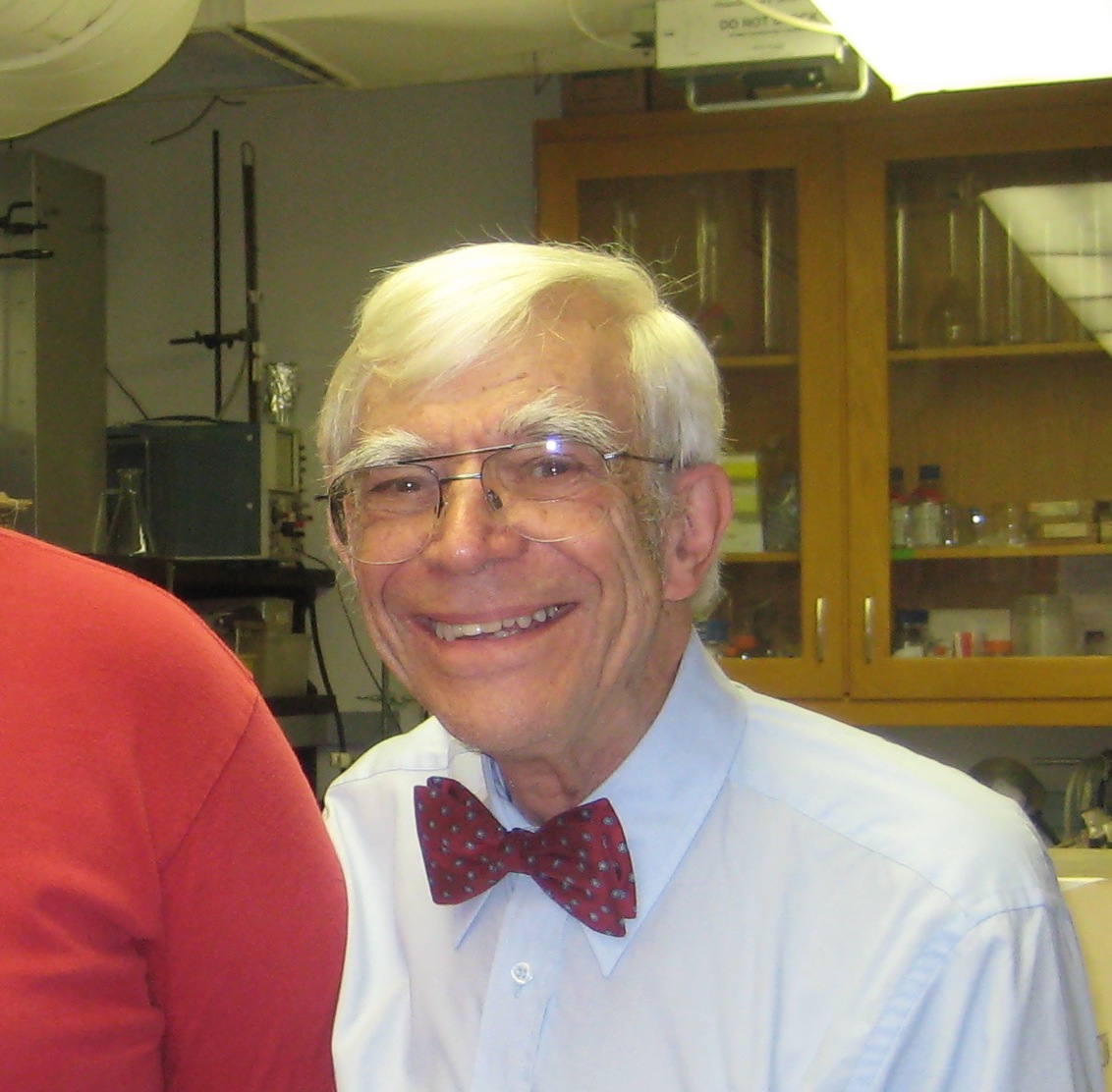

Dr. Van Middlesworth worked for over 60 years at the University of Tennessee medical school. At the age of 90 he became the inspiration and driving force of AFH’s work in iodine deficiency. He is a inspiration to all of those who meet him. Please take a moment to read these two articles about this man.

#1: Buck Rodgers of the 21st century

#2: A science lab closes, but its muse, 91, carries on.

As he has almost every day since he arrived on campus in 1946, Lester VanMiddlesworth wore a bow tie Thursday. But on this special day, he was wearing a red carnation pinned to his thin blue sweater as well.

VanMiddlesworth, nicknamed “Van,” was the star of a social hour celebrating his achievements as a physiologist at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center, on the occasion of the closing of his lab (he officially retired in 1989). He is 91.

As a child, he spent his days daydreaming about science, inspired by radio broadcasts of “Buck Rogers in the 25th Century,” and buying a nickel’s worth of charcoal, saltpeter and sulfur at the local drugstore for his homemade basement chemistry lab. He idolized Thomas Edison, who died when Van was 12, and adopted Edison’s habit of sleeping just four hours a night.

In college at the University of Virginia, often penniless, he earned money sweeping the gym floor and answering phones for a taxicab company. He’d sneak naps on the floor of Edgar Allan Poe’s old dorm room.

While working on the Manhattan Project as a graduate student at the University of California at Berkeley, he slept on the lowest shelf of his lab.

After moving to Memphis in 1946 — and meeting a beautiful Smoky Mountain nursing student named Rue, his future wife (and lab assistant who worked for free, a “husband’s discount,” she joked) — he began studying radioactive iodine in the thyroids of cows that were ingesting the radiation from nuclear-testing fallout drifting through the atmosphere. His work was so pioneering and so invaluable that it was crucial in the development of the global Nuclear Test Ban Treaty; his findings are now on display in the Smithsonian Institute.

Van was already retired when his department head, Gabor Tigyi, arrived in 1992, but, Tigyi said, “He has been the most passionate man I have ever known. His lab” — he stopped, as if struck by the mental image flashing through his mind — “it’s like, wow, the workshop of a mechanic or an inventor or even a mad scientist. So much beautiful chaos, so many half-finished projects; the kind of lab that is a shrine to the mind and wonderful thinking.”

The author and editor Phyllis Tickle, also in attendance, calls Van “a muse.”

Van’s commitment during his time on campus was extraordinary. “I didn’t come to leave,” he said matter-of-factly at Thursday’s reception.

Van handled the animal cages himself, scrubbed the floors himself, paid out of pocket to attend conferences or speak at far-flung awards ceremonies, often staying at the local YMCA (until the school found out and gave him a travel budget). When academics would visit, he insisted they stay at his home and not at some impersonal hotel — a habit that made for interesting dinner conversations with his wife, their two sons and two daughters.

Spry and cheery with thick, floppy white hair, he can seem bounding with energy even while leaning on a cane. When a neighbor broke her leg three years ago, he surprised her by mowing her lawn for her. Until recently, he rode his bicycle to and from work.

“There are two types of teachers,” said Abbas Kitabchi, an endocrinologist colleague, in an address to the crowd of about 140 people, including Van’s children and grandchildren, “those who can’t be forgiven and those who can’t be forgotten. Van is the latter. His teaching is legendary and he himself is a legend.”

Kitabchi began choking on his words; Van put a hand on his shoulder before grudgingly becoming the center of attention himself.

When the time came for Van’s own speech, 64 years of service were distilled into 8 words: “I can’t say anything, except: thank you, all.”

Later, in the thick of welcoming the receiving line that snaked around the room, he said of leaving that “if you tear off a chunk of yourself — and that’s what you’re doing when you leave everyone you’ve known — it can’t quite be done. It’s artificial. You can’t really be separated.”

Then he grabbed the next handshake with the next grateful student-turned-colleague-turned-friend and joked: “See?” he smiled, his hand squeezing tight, “We’re inseparable.”

http://www.commercialappeal.com/news/2010/oct/15/a-science-lab-closes-but-its-muse-91-carries-on/

Published by